In 1989, an unpromising-sounding however alluring marble sculpture of a feminine nude got here up on the market at a Christie’s public sale held at an English nation home in Hertfordshire. {The catalogue} claimed it was “an 18th-century white marble half-length determine of Venus Marina”, however the London-based vendor Patricia Wengraf knew higher.

“It was clearly Giambologna’s Fata Morgana,” she says, of what had been thought to be a misplaced work by the revered Flanders-born Italian Mannerist sculptor (1529-1608), courting to the early 1570s. In 1998 Wengraf bought it to a personal European collector, and right this moment the Cleveland Museum of Artwork revealed that it has acquired the sculpture for an undisclosed sum. Wengraf dealt with the sale.

One in every of solely a dozen surviving works in marble by Giambologna and set to be solely the second within the US, the Fata Morgana (round 1572) has dramatic implications for the museum, says its director William Griswold. “This is among the most vital acquisitions made in additional than a decade,” he says, invoking by means of comparability the museum’s 1997 buy at public sale of Marilyn X 100, an almost 19ft-long 1962 work by Andy Warhol.

The opposite marble sculpture by Giambologna within the US, one other nude dated to 1571-73, was purchased by the Getty in 1982. The one different Giambologna marble in a group exterior Italy is his Samson Slaying the Philistine (1560-62) on the Victoria and Albert Museum.

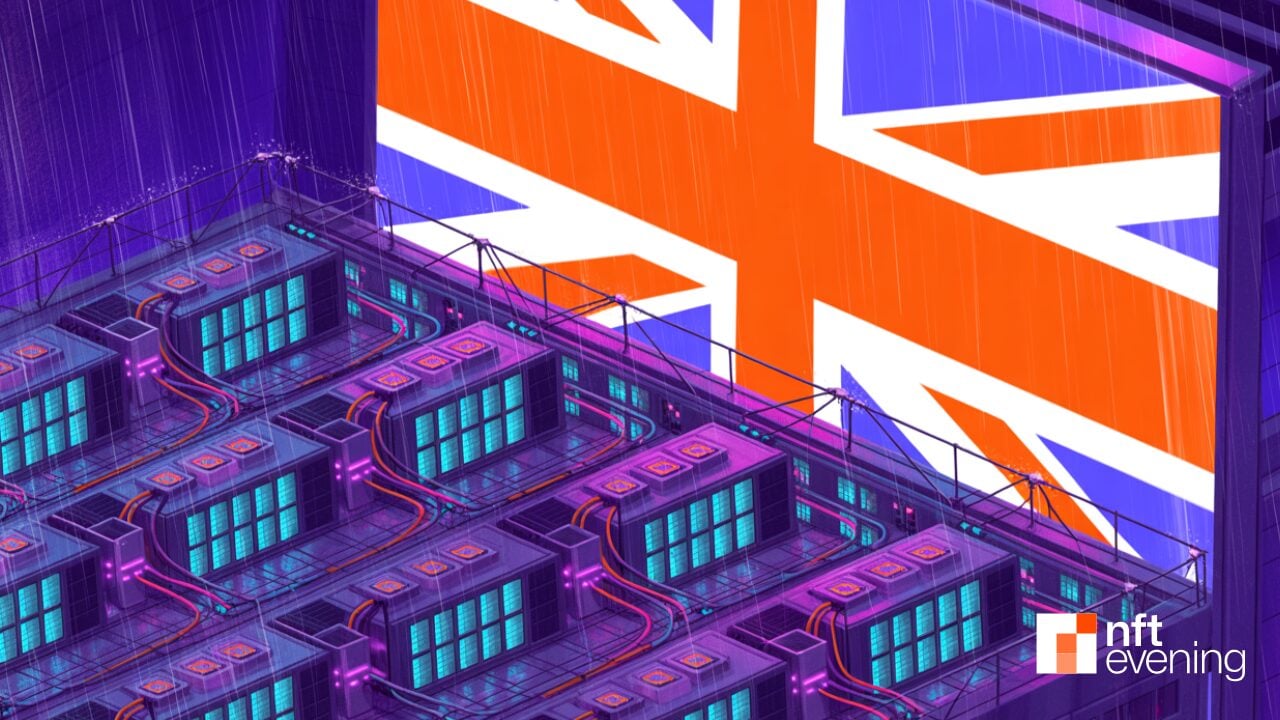

Giambologna—a local of the Flemish city of Douai, now in France—made his approach to Italy within the early 1550s, ultimately settling in Florence. A Medici favorite, he created the Fata Morgana for a constructed grotto on the grounds of a villa exterior Florence, owned by a banker for the Medici household. A close to life-size work, it stood above a basin that obtained water from a flowing spring. The museum plans to recreate that grotto setting in its new set up.

Again in 1989, Christie’s says, the pre-sale estimate for the work was £3,000 to £4,000, nevertheless it finally bought for £715,000. “I wasn’t the one one that realised {the catalogue} description was utterly mistaken,” Wengraf says of the heated bidding. Following its sale to the European collector in 1998, the work was ceaselessly on view in exhibitions, together with a landmark present in Florence in 2017-18, The Cinquecento in Florence: Fashionable Method and Counter-Reformation, on the Palazzo Strozzi.

Its identification because the work as soon as thought misplaced is now well-established. “I’ve little doubt that that is the Fata Morgana by Giambologna,” says the Florence-based artwork historian Antonio Natali, the previous director of the Uffizi Gallery and co-curator of the Palazzo Strozzi present.

Giambologna, Fata Morgana, early 1570s (element) Cleveland Museum of Artwork. Picture courtesy of Gary Kirchenbauer

The Cleveland Museum of Artwork first turned conscious that the work was on the market a bit over a yr in the past, says Alexander J. Noelle, the assistant curator of European work and sculpture, 1500-1800. Noelle, who had seen the work on the Strozzi present, says that he and his fellow European artwork curator in Cleveland, Cory Korkow, “had been floored” once they came upon.

The group is particularly happy with the situation of the piece. Since arriving on the museum, says Noelle, it has solely wanted minor in-house conservation therapy. Different Giambologna marbles, Korkow says, had been sometimes stored exterior and “skilled extra weathering”.

In its authentic setting, the sensuous nude, customary out of Carrara marble, was a part of an ensemble that included a spiritual fresco exhibiting Jesus with the Samaritan lady, a Biblical scene set close to a nicely. This distinction was of nice significance to the organisers of the Strozzi present, who regarded the juxtaposition of the profane sculpture with the sacred fresco as reflective of Florentine sensibilities within the second half of the sixteenth century.

In its new grotto-like residence in Cleveland, the curators plan to place it because the “linchpin of our complete Renaissance and Mannerist collections”, says Noelle. Set in a serious sightline, it should “beckon you” into the galleries displaying Quattrocento and Cinquecento artwork, and might be close to a staircase that leads as much as the Baroque collections, he says.

The museum, which already has two bronze sculptures related to Giambologna, are treating the brand new acquisition as an event to launch “no less than one or a number of exhibitions” that may function the work, doubtlessly together with one that appears on the matter of magnificence within the Mannerist interval, says Noelle.

The museum’s new acquisition will go on public show in Cleveland on 30 August.